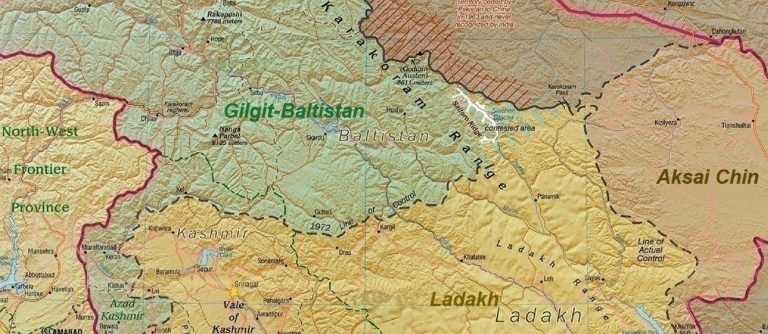

In 1856, the Maharaja Gulab Singh ruled the Princely State of Jammu and Kashmir, with the blessing of the British. Lieutenant Thomas George Montgomerie, the commissioner of the Great British Trigonometric Survey of India, was trying to ascertain the heights of the peaks in northwestern Kashmir, but he couldn’t actually get close to ones he wanted to measure: He was ordered not to cross the Indus River, in order to avoid the rumoured “unfriendliness of the Gilgit people”.

Instead, they managed to set stations on a series of peaks, some above 5,000m and not easy climbs. Once, a fierce storm trapped them at an altitude for 22 days. When they climbed the sacred summit of Mount Haramouk (5,142m), which the locals considered the home of the god Shiva, Montgomerie spotted two prominent peaks about 200km to the north, in the Karakoram. He sketched and tagged them K1 and K2.

Those were not meant to be their definitive names; the surveyors planned to later assign to them their proper local names. In the case of K1, they soon confirmed that the Balti people knew it as Masherbrum. The more remote K2, however, did not appear to have a name. Surrounded by gigantic glaciers and secondary massifs, it was out of sight of all the villages in the area. The most the researchers could coax from the Balti in Askole was something like “Chhogo ri”, literally “Big Mountain”. It was not clear whether that was its actual name or just a description of the peak. The surveyors soon determined that the semi-anonymous mountain was taller than all others in the region.

One of Montgomerie’s team, Henry Godwin-Austen, conducted some remarkable explorations in the Karakoram. He reached the base of Masherbrum and K2 and fixed both their heights and exact locations. What was “temporarily known as K2” was found to be 8,623m — “second only to Mount Everest,” as one official of the time pointed out. That early measurement was uncannily accurate: today, K2’s official height is 8,611m.

The mountain could easily have been re-labelled after some prominent member of the Trigonometrical Survey, as Everest had been, but it wasn’t. Godwin-Austen gave his name to the huge glacier at the base of K2, but although his name was also put forth as a candidate for K2 (and still so appears on some maps), he ran afoul of the Geographic Society, which refused to grant him the honour. What his political faux pas? He had had the “very undesirable” idea of falling in love and marrying an Indian woman. This also kept him from advancing further in the civil service of the time.

Years went by, and explorers ventured into the Karakoram until finally, they stood face to face with the mighty pyramid. In 1954, nearly a century after Montgomerie and Godwin-Austen’s findings, Italians — Lino Lacedelli and Achille Compagnoni — stood on the summit for the first time.

And yet, the name K2 remained. Chinese or Urdu names didn’t manage to become popular. Eventually, no other name could fit the peak. Even the Balti people know it as K2, or in Balti pronunciation, Kechu or Ketu. George Bell, a member of Charles Houston’s 1953 American expedition, dubbed it the ‘Savage Mountain’ because, as he told reporters, “It’s a savage mountain that tries to kill you.” That nickname has stuck.

By the way, Montgomerie’s original survey listed three other “K” peaks: K3, K4 and K5. These eventually became Gasherbrum-IV (the Shinning Mountain), Gasherbrum-II and Gasherbrum-I (Hidden Peak).

More about the Great Trigonometrical Survey of India in this documentary:

This feature was first published in ExplorersWeb online news magazine.

![]() Angela Benavides is a sports journalist, author and communication consultant. Feeling back home at ExplorersWeb after five years exploring distant professional ranges.

Angela Benavides is a sports journalist, author and communication consultant. Feeling back home at ExplorersWeb after five years exploring distant professional ranges.

@angelab

The High Asia Herald is a member of High Asia Media Group — a window to High Asia and Central Asia