Impact of increase in shrubs and grasses not yet known but scientists say it could increase flooding in the region

Shrubs and grasses are springing up around Mount Everest and across the Himalayas, one of the most rapidly heating regions of the planet, says a report published in The Guardian, London.

Scientists used satellite data to identify increases in vegetation in the inaccessible subnival (the highest zone allowing plant growth) ecosystem, made up of grasses and dwarf shrubs with seasonal snow. This ecosystem is known but could play a crucial role in the region’s hydrology, covering between five and 15 times the area of permanent glaciers and snow in the region.

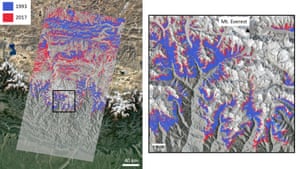

Studying images from 1993 to 2018 provided by Nasa’s Landsat satellites, researchers from Exeter University measured the spread of vegetation cover across four height brackets from 4,150 to 6,000 metres above sea level, the report says.

The melting of Himalayan glaciers has doubled since the turn of the century, with more than a quarter of all ice lost over the last four decades. Research has suggested that its ecosystems are highly vulnerable to climate-induced shifts in vegetation.

“A lot of research has been done on ice melting in the Himalayan region, including a study that showed how the rate of ice loss doubled between 2000 and 2016,” said Dr Karen Anderson, of the Environment and Sustainability Institute on Exeter’s Penryn Campus in Cornwall.

“It’s important to monitor and understand ice loss in major mountain systems, but subnival ecosystems cover a much larger area than permanent snow and ice, and we know very little about them and how they moderate water supply.”

It is not yet known how more vegetation might affect water supplies but studies of increased vegetation in the Arctic found that they delivered a warming effect in the surrounding landscape, with the plants absorbing more light and warming the soil.

But Anderson said that more vegetation may not actually increase warming and flood risks in the Himalayas, with the only study in the region, in Tibet, finding that the water in the plants that is evaporated through their leaf surface actually exerted a cooling influence.

The study, published in Global Change Biology, was made possible by Google’s new Earth Engine, which provides researchers with a freely accessible collection of government agency satellite data in the cloud. Previously, researchers would have had to build a super-computer to sift through the enormous quantities of satellite data.

“It has really revolutionised this kind of work and enables large-scale, long time-series investigations like this to happen,” said Anderson.

The High Asia Herald is a member of High Asia Media Group — a window to High Asia and Central Asia