Since July, the courts have handed down more than 5,000 verdicts with heavy sentences against members of a Shiite Ismaili ethnic group. About 100 detainees, including seven journalists, are awaiting trial.

Authorities in Tajikistan have forced the closure of two religious bodies in the capital Dushanbe within a succession of a week, according to media reports.

The institutions are the Ismaili Tariqa and Religious Education Board, or school, used by adherents of the followers of Prince Karim Aga Khan, and a bookshop trading in Islamic literature.

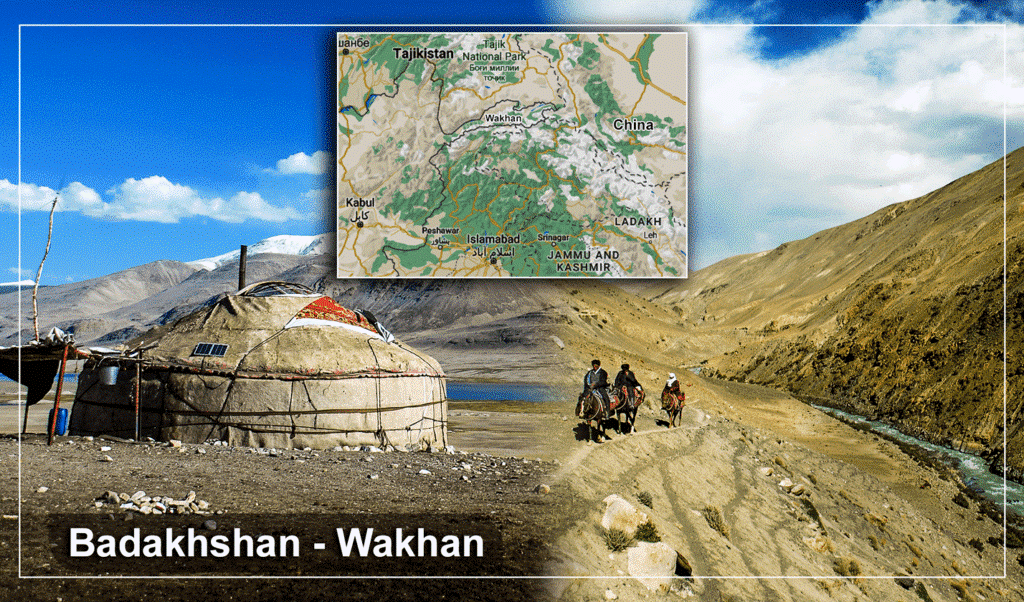

The broadside against the Ismailis, a splinter group of the Shia Muslim faith, fits within a broader pattern of repression of Pamiris, a roughly 230,000-strong minority whose historic homeland in what is known as the Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Region, has been subjected to sustained security sweeps over recent months.

ITREB was registered in 2012 at the same time as the opening of the first Ismaili Center in Dushanbe. The location was used by followers of Ismaili Shiism for both secular and religious education.

Sources at the centre told Eurasianet that they have been under pressure from the authorities since May to suspend their educational activities. It has been several weeks since the doors of the premises have been closed to the public.

The Ismaili Center, which houses, among other things, a jamatkhana, a place where followers of the faith gather to pray, remains open, although its future also looks bleak in light of the evolving situation.

The state’s religious affairs committee has made no public statement on the closure of the Ismaili Tariqa and Religious Education Board. Three years ago, however, the committee sent a letter to the organization expressing discomfiture at the fact that the portrait of the Ismaili faith leader, the Agha Khan, had been hung above that of the president, Emomali Rahmon.

In the eyes of the government of Tajikistan, no figure holds a more hallowed status than Rahmon.

Official intolerance toward religion extends further than just the Ismailis, however. The government has taken a hostile stance against Islamic education in general. A decade ago, all the country’s madrasas were shuttered under the pretext that the Education Ministry was drawing up a sanctioned religious curriculum. The doors of the country’s six madrasas never reopened, however.

This past week, the authorities forced the closure of the only bookstore in Dushanbe dealing in religious literature. A spokesman for the state religious committee said the closure was temporary, pending an inspection of the store’s catalogue.

All this has happened despite the fact that around 95 percent of Tajikistan’s population self-describes as Muslim.

The only remaining place for pursuing studies in religious matters is the Islamic Institute in Dushanbe, which lies close to the now-shuttered bookshop. Ninth-grade schoolchildren are also required to complete a History of Religion unit.

The clampdown on religion is even more extensive than that.

Children under the age of 18 are forbidden from visiting the mosque. People under 35 are ineligible to apply to perform Hajj (pilgrimage) to Mecca.

Prayer is not allowed in government institutions and members of the public are in effect prohibited from entering government buildings while wearing a hijab or beards grown as a symbol of Islamic piety.

There are no courses available for the study of Arabic. Young people pursuing religious studies have been forcibly repatriated over the past several years.

The only legally operating imams are appointed by the religious affairs committee, from whom they draw a salary. Their sermons are prepared in advance by the committee. Countless mosques have been closed. Little prayer rooms dotted around the country have often been dismantled.

This is all a boon to recruiters of underground groups professing radical forms of Islam. The most notorious of these, the Islamic State, has made the fact of the Rahmon regime’s repression of blameless Muslims a core pillar of its recruiting rhetoric.

The chronology of violence in GBAO

Kholbash Kholbashov, a former head of the Gorno-Badakhshan border guards, and his ex-wife, Ulfatkhonim Mamadshoeva, a journalist and activist, were sentenced to life and 25 years’ imprisonment respectively by a court in Dushanbe on August 15, for “terrorist organization” and “violently calling for a change in the constitutional order.” Both belong to the Pamiri minority, an Ismaili ethnic group present in eastern Tajikistan – as well as near the borders of Afghanistan, China and Pakistan – which has long been targeted by the government, says a report in French newspaper Le Monde.

Mr Kholbashov and Ms Mamadshoeva are accused of inciting the protests that took place in May in Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Oblast, where several thousand Pamiris protested for the respect of their rights and against the repression they have been subjected to since November 2021, after the Pamiri sportsman Gulbuddin Ziyobekov was killed by Tajik police. The protests peaked on May 14, particularly in the districts of Khorog and Rushan on the border with Afghanistan. Four days later, the Tajik government launched an “anti-terrorist” operation to contain the movement, which had become massive in the Gorno-Badakhshan region.

Read more Bloody crackdown on the Tajik ‘roof of the world’

Since then, the crackdown has continued to intensify, with mass trials handing out heavy sentences, including life imprisonment, to not only the leaders of the Pamiri movement but also all activists from the ethnic community.

According to the exiled Tajik journalist Anora Sarkorova, “the authorities want to imprison so many people that they have gone to build another women’s prison, in the Sughd region in the north.”–Eurosasianet/Le Monde